The Impure Apparatus (Presentation at EARN conference, Leeds)

Alan writes:

I was able to present our project at the recent annual conference of the European Artistic Research Network, which this year took place in Leeds and was organised by Azadeh Fatehrad, Maki Fukuoka and Nick Thurston. Here are the slides and films from my presentation, with the script superimposed in subtitles and in lugubrious voice over (the argument is intended to be playful and so the voice performance is not so apt, but I neglected to record my more lively performance on the day). The full script is also printed below, and represents a first attempt to take stock of the whole project and to think about how we might summarise and analyse it in a future film and/or article. This presentation has benefited from feedback to a talk on the project that I gave at The Ohio State University in September as a guest of Dana Renga. Comments from Shannon Winnubst and from Roger Beebe were particularly useful for me and I want to thank them both for their generous engagement with the work.

Script

I’m going to talk today about Parameters & Practice, a collaborative project between myself and my partner, Marie Hallager Andersen, which we undertook between October 2018 and October 2019. Marie can’t be here today because she recently gave birth to our second child, but she has collaborated on the preparation of this paper. The birth of our child generated the final task and response of the project and so signalled the end of the project itself; this presentation is the first opportunity we’ve had to take stock of the project.

The format of Parameters & Practice was as follows. Each week, one of us set a task for the other. The second person performed the task and recorded a response, and the following week set a further task for the first person. And so on for fifty-one tasks and responses over the course of the year. These tasks and responses were posted on our project website on a roughly weekly basis.

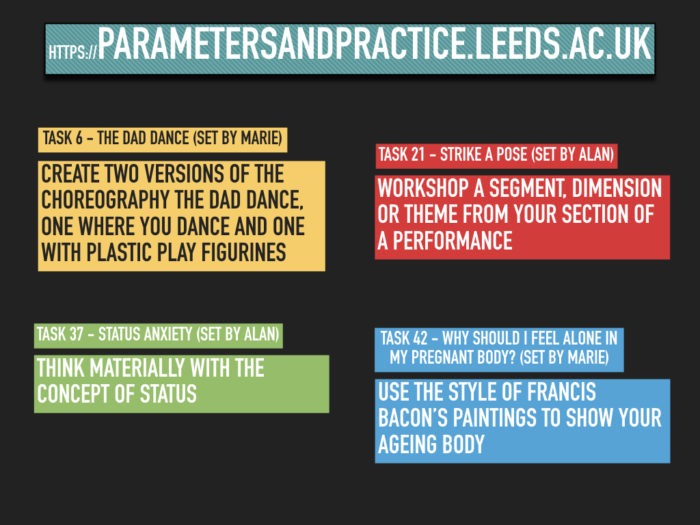

On the slide are four examples of tasks set—presented here in summary (the actual text of each task would have been longer, and a context and rationale usually provided). The tasks we set could be more or less cryptic or specific, and more or less constrained, and they usually specified an activity or practice. Tasks could pick up on previous concerns or not. Sometimes a series of tasks over a number of weeks took a kind of relay form, while some tasks had little or no connection to previous tasks or responses, though all of the tasks set tended to derive from conversations and arguments we were having, and certain themes emerged and recurred across the year.

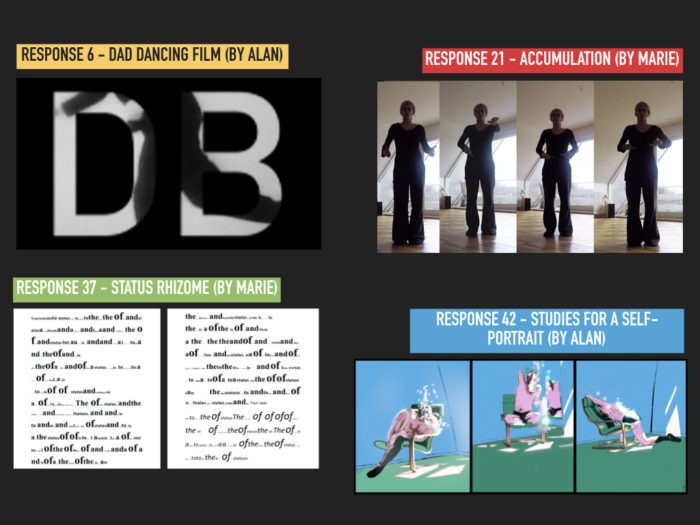

This slide shows the responses to the four tasks on the earlier slide.

I’ve chosen this selection—two from Marie and two from me—to give a sense of the variety of undertakings. Response 6 and Response 21 take the form of dance films. Response 37, on the other hand, is a deformative prose piece, and Response 42 is an exercise in the mimicry of Francis Bacon done as a kind of cartoon.

In these four cases, the response to a task has generated a product, but this was not always the case—sometimes the response was limited to an activity, though this would always have been accompanied by an account of process on the project website, which could be lengthy and involved, or cryptic or short (see the examples, mentioned above, of the brief Response 37 and of my own long-winded account in Response 42).

I think the project website constitutes a sketchbook of ideas for future development, but I think I can speak for Marie when I say that we’re a little ashamed of most of the individual responses, which were often over-ambitious even as they were produced at speed and sometimes in trying circumstances. But for us, more important than any individual response was the iterative character of the project: its relational, ludic and agonistic character of regular exchange. We described it to ourselves as a ‘meta-project’: the concern of Parameters & Practice was not with a particular content or theme; it was with the activity of the project itself, and, as I will explain in a moment, it was with how the project allowed us to be together.

The choice to present the project on the Leeds University website was made with an eye to future activities, in particular funding applications and REF (the national research assessment exercise for UK universities).This explains a certain aspirational cast in the characterisation of our project goals and motivations, when we state: ‘The object of this project is to offer a model for artistic/academic collaboration and to develop the mechanisms and protocols for innovative creative research.’ It’s fair to say that a more powerful motivation for the project was not to do with providing any models, but with the challenge of being life and love partners at the same time as being creative individuals.

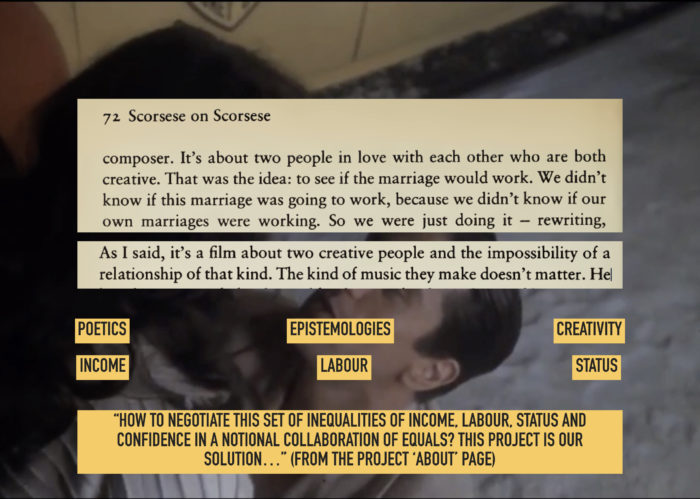

Allow me a digression, here. I don’t know how many of you know the Martin Scorsese film New York New York—it’s not one of the director’s most loved or best known works. But it interests me precisely for its concern with the possibility of a creative relationship: in fact, Scorsese says in an interview that his film is about two creative people and the impossibility of a relationship of that kind.

If New York New York was about a creative relationship, and concluded that it was impossible: could our project successfully enact a creative relationship? Could we live together and still work together? Could we work together and still love each other?

With questions like these in mind, the project was designed to identify and interrogate a set of differences and inequalities between us. Differences to do with aesthetics and poetics—what kind of knowledge and what kind of art we each valued and our sense of how these should be produced. Inequalities to do with income, status, and labour—whether artistic, academic or domestic. The project was our way of negotiating this set of differences and inequalities.

I could mention several models for the Parameters and Practice project, particularly for its task-setting dimension. But the one I want briefly to discuss today is the film The Five Obstructions by the Danish filmmakers Lars Von trier and Jørgen Leth. In this film, Von Trier sets Jørgen Leth the task of remaking the latter’s 1960s classic short film The Perfect Human, according to five sets of perverse constraints—these are the obstructions of the title. Here are some clips from the film.

The Five Obstructions has inspired some excellent scholarship, and an article on the film by the artist Hector Rodriguez has particularly informed our thinking about our project. Rodriguez uses parametric or constraint-based approaches in his work, and in his article he asks an interesting question. He asks if constraint-based work generate only closed systems, or if it can instead as he says ‘open up to the life lived during its making’. For our own purposes, we initially glossed Rodriguez’ question as follows:

Does the apparatus of the Parameters & Practice project allow better access to the life lived and experienced than an approach directly concerned with that life or experience?

Now, there are a number of problems with that question as it is phrased here. It suggests a long discredited idea of lived experience able to speak for itself, as if any framing of experience wasn’t always-already an interpretation, or as if experience itself was not discursively produced. In order better to characterise the activity and affordances of the Parameters & Practice project, I want to consider the project as an apparatus.

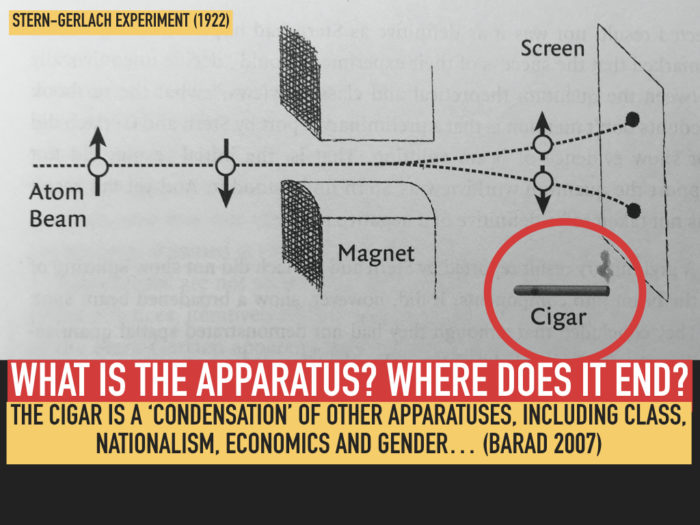

Some of you will be familiar with this diagram from a book by Karen Barad, which illustrates the 1922 Stern-Gerlach experiment in quantum physics. Don’t worry about the quantum physics: what’s important for our purposes is Barad’s characterisation of Stern and Gerlach’s experimental apparatus. Famously, the results of the Stern-Gerlach experiment remained invisible until Otto Stern peered at the screen close to and breathed on the plate shown on the right of the diagram. As a junior lecturer on a low salary, Stern was obliged to smoke cheap cigars infused with sulphur, and it was only the interaction with the plate of Stern’s sulphurous breath that revealed the experimental results. For Barad, the vital point is that the experimental apparatus in this case cannot be limited to the laboratory setup somehow pictured as distinct from human, but more particularly discursive intervention. That is, the apparatus has to include the cigar.

But, Barad says, the cigar itself is a ‘condensation’ of other apparatuses: class, economics and gender among them. And these other apparatuses cannot be excluded from the description of the workings of the Stern-Gerlach experimental apparatus. The exciting conclusion that Barad draws from this account of the Stern-Gerlach experiment is that there is no intrinsic outside to the apparatus.

What has this got to do with Parameters & Practice? I’ll mention two aspects.

Firstly, Parameters & Practice is an impure apparatus constructed deliberately to include its outsides. The project potentially makes part of the undertaking all the outside bits that would conventionally be excluded in an academic project certainly: friends that visit, whims and occasional concerns, reading, travel, life events, not to mention those multiple discourses of class, nationality and gender mentioned by Barad… All of these fed in to the laboratory of our task-setting and the texture of the responses.

Secondly: we follow Barad in conceiving of the apparatus as a performative rather than a descriptive or representational mechanism. In other words, as an apparatus, Parameters & Practice didn’t reflect or describe our world, or reflect or describe the life lived by the project partners during its duration: instead, the project helped to make that world; Parameters & Practice intervened in the form that life would take during the project and beyond.

How effective was this impure, performative apparatus? To answer this question, let me return now to the explicit ‘institutional’ rationale we provided on our website for the Parameters & Practice project: ‘The object of this project is to offer a model for artistic/academic collaboration and to develop the mechanisms and protocols for innovative creative research.’ ‘If the object of the project was to provide a model and mechanisms for future work, whether by ourselves or others, we have to admit that the project has been a failure.

In my response to the final task set by Marie, I admit as much. As I say there, we haven’t actually been able to figure out how to work together in the future; we didn’t achieve any convergence in our individual poetics; the project didn’t bring us ‘closer’ as scholar-artists. Instead, it foregrounded and cemented an incommensurability in our creative personalities.In short, the project has failed if what the apparatus was meant to generate was a generalisable model for artistic/academic collaboration. But in at least one other respect, maybe not. Here’s an extract from the film made in response to the final task, with a recording of a conversation about the project on the soundtrack.

What I have suggested here is that the performative apparatus of the Parameters & Practice project helped to make the world; it intervened in the form that life would take in a very literal sense: it helped to make a baby. And in that sense,the project has been a notable success.

Now, this assertion could be making you queasy for a number of reasons. I’ll mention three. Firstly—maybe because it seems to express what queer theory calls reproductive futurism: the thoughtless consensus that maintains a heteronormative social order in the name of ‘The Child’. Secondly—maybe because it seems a complacent expression of privilege: oh, whoopee! yet another white cis-gender straight couple oversharing the fact of their nauseating fecundity. Thirdly—maybe because it seems to efface the reality of pregnancy as a mode of being-in the world, something that Marie had deliberately confronted over the course of the project.

Still, these three criticisms notwithstanding, I hope there is a value in how the Parameters & Practice project functioned to perplex the reified identities of academic and artist: the project generated the collaborators as the culmination of their practices—practices that included dancing, writing, drawing, parenting, filmmaking and so on—so that our identities were revealed as the sum rather than the source of those practices and we were allowed to be constantly in-becoming.

So, I hope I can insist on the value of a project that has led to a birth of a child rather than the drafting of a funding bid. It turns out that the impure apparatus that we constructed with Parameters & Practice was a love machine.