Task 37 - Status Anxiety

Alan writes:

Your task this week is to think materially about ‘status’. When we were setting up this project, we both wrote introductions to post on the project About page. Here are two snippets on the theme of equality and status – a longer one from mine (as prolix as this task) and a shorter one from yours.

Marie and I have talked about developing a collaborative and hybrid art/academic practice for some years. We have postponed collaboration until now for the usual logistical reasons, but also because issues of equality and status seemed difficult to overcome. I am a university lecturer on a decent salary, whereas Marie is an independent dance artist and freelance yoga teacher and life coach with uncertain income. As a senior academic, I am charged with time-consuming administrative responsibilities to my school and faculty, while Marie undertakes the bulk of domestic and childcare work in our household, even as she juggles the various facets of a ‘portfolio career’. My academic position and title (‘professor’) have a high cultural status whereas Marie’s work is seen by some (not me!) to be socially marginal or to be a lifestyle luxury. Conversely, Marie’s long experience of artistic work means that I might feel myself a junior partner in any creative undertaking. How to negotiate this set of inequalities of income, labour, status and confidence in a notional collaboration of equals? This project is our solution. (from Alan’s project introduction)

The inequalities of our relationship (status, income) and the roles we have taken on/been given (parents, main breadwinner) will be laid bare and negotiated. (from Marie’s project introduction)

Status is dynamic and relative. It changes, and it changes in relation to others, and it’s this dynamic and relative character that I hope you can investigate. Our negotiation of status and equality relative to each other happens in a social context where the individual status of each of us is likely to be constantly shifting, even if at different rates. I am setting a task on this theme because I have a sense of my own ‘dwindling’ status within my job. (Yes, I am conscious of the narcissism of this.)

My personal sense of crisis, alluded to in Response 36 and resulting from uncertainly about my future and a series of rejected funding and fellowship applications, is part of a broader anxiety concerning the changing conditions of the academic workplace. There is increasingly a feeling in the UK academy that you are never quite ‘there’ career wise, and that your status within your institution is always contingent on future success rather than past achievements. In fact, the UK academy is witnessing something like a crisis of mental ill-health (at the very least, there is an epidemic of anxiety and insomnia). This has been described in a recent report by Dr Liz Morrish for the Higher Education Policy Institute, which blames the crisis on the audit (and surveillance) culture of UK universities and increasingly large or complex workloads and ‘performance’ expectations.

Morrish also notes that ‘many academics exist on a succession of precarious contracts which do not allow for career planning or advancement’. This is an important point, and it may suggest that status anxiety is a privilege of those (like me) lucky to have stable positions and salaries. Who cares what anyone else thinks of you, it might be suggested: after all, as long as you have enough money, you can just cry all the way to the bank, no? Research does not bear out this objection. My Leeds colleague Sarah Waters has done important work on workplace suicides in France and other countries. She talks of workplace suicides as giving ‘material embodiment to relations of production in the form of extreme human suffering’. I remember her explaining that testimony written by workers in one huge French firm who went on to kill themselves made it clear that a key motivation for taking their own lives was their ‘redeployment’ (HR doublespeak) to jobs of a lower skill level, perceived to carry a lower status. Sarah’s research demonstrated that the perception of erosion of status is a key factor in workplace unhappiness; it reveals as pop-Buddhist myth the idea that status is an illusion: as individuals we function relative to others and to our societies, and our sense of self-worth is not intrinsic but contingent. Status structures our world.

So: how does status structure your and my shared world?

Your task

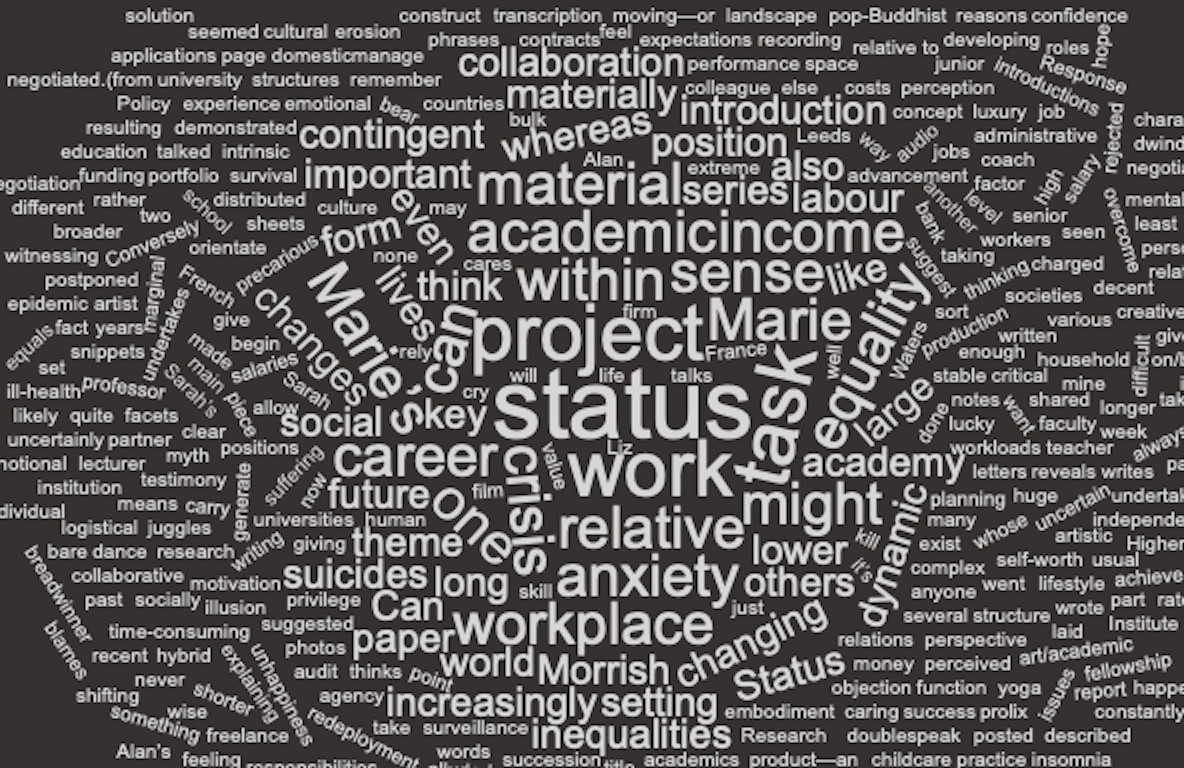

I want you to work (think materially) with the concept of status. The material thinking might generate any sort of product—an audio recording, piece of writing, series of photos, film of you moving—or none, but it should begin with the transcription on paper in large letters of several words or phrases from the text of this task (i.e., the material on this webpage). The sheets of paper should then be distributed in a space.

Can you manage to orientate yourself within this landscape? Can you construct a critical as well as a ‘survival’ perspective within this landscape (critical also, perhaps, of the way I have framed the issue of status)? What form can agency take when we rely on our social position to give value to our lives? What are the costs in emotional labour of caring for another who feels their status is under threat?